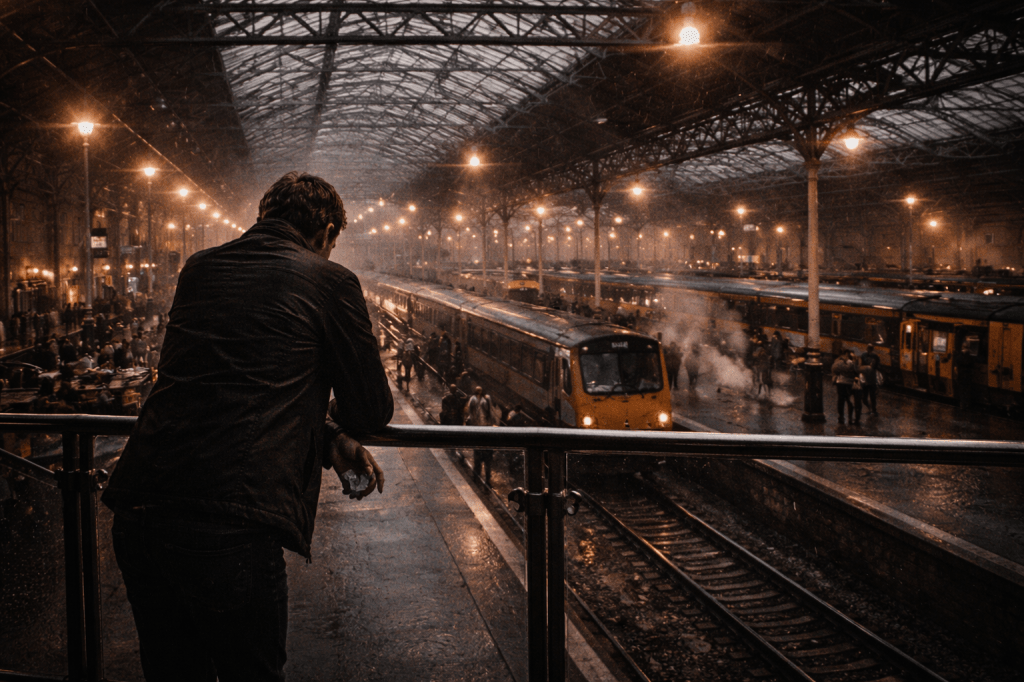

Stood there on the concourse at Waverley with the whole sky slung low like a tired curtain, a bruise-grey canopy that pressed its weight on the rooftops, and the glass canopy gleamed in its own cold mutter, and the trains below rumbled their iron-lung prayers, long breaths, deep breaths, and the grimelectric of departure vibrated through the steel ribs of the station into my own, and I had the ticket in my hand, a wee slip of almost-freedom burning its paper heat into my palm, and I told myself—quiet, inward—lad, this is it, time tae leave, time tae outrun the ghosts, time tae find some place that disnae keep speakin’ in the back o’ yer heid every time the light hits the pavement wrong.

And the tannoy crackled its crack-crackle nonsense, announcing cities I’d never seen and ones I swore I’d never bother with, and the trains hissed like great restless beasts tired of being leashed, and folk dragged their wheeled suitcases in wee rattling pilgrimages, and boots clacked on tile, and the whole station resembled a heart made of travellers, pulsing, pulsing, a throbbing organ of folk wanting out or wanting home or wanting somewhere that did not weigh quite so heavy.

And me—leaning against the barrier rail, the Salamander Street spark still twisting in my ribs, Dalry’s nightshift neon circus clinging to my clothes, Haymarket pintwarmth lingering at the back of my tongue, the schoolyard mitten ghosting its small ache at the base of the spine, and the long-ago boy who ran through Slateford glass still hitching a ride in the marrow—all of them inside me like coiled-up threads wanting to pull in different directions. But the station—och, the station—it has its own gravity. A city’s throat. A city’s open mouth inhaling and exhaling lives.

The air had that iron and stories and perfume and commuter sweat, and the great curved roof reverberated with pigeon chatter and the dimdim dusk of fluorescent halo-light, and the whole place shimmered in my eyes like an enormous Lung of Leaving, beating slow, beating sure, dragging people out into the world. And I stood there, and felt the pull, the pull to step onto the train, to let the doors hiss shut, to watch the city melt backwards through the window like a postcard dissolving in rain, to become a blur, a smudge, a noise I used to know.

But the city, sly bastard it is, whispered sideways—no voice, no language, just a flicker of neon caught in the corner of my eye, a shimmer like the tail-end of her laugh from Salamander Street, a ghostsmile surfacing in the glass of the departure boards, the faintest spark that said: aye lad, but haven’t ye still got a few things left tae listen to?

And something in my chest buckled, that sudden recognition that the world outside the ancient city looked too flat, too smooth, too unflickered, as if it had no dark closes that stretched impossibly long, no delis crying out their 3AM electric gospel, no pubs where glass clink and banter blur into soft-lit absolution, no foxes swaggering like kings of the night, no neon women leaving bright echoes in puddles, no ghost-boys hiding in the marrow, no sandstone breath, no cobblestone pulse.

I walked halfway to the platform, and I felt the ground tilt beneath me like a great stone beast shifting its weight, and I heard the train cough a welcome, and the doors opened like the split mouth of a future I wasn’t sure about, and for a heartbeat I stepped inside the idea of leaving, felt it wrap around me like a coat too heavy for the season.

Then the sounds changed. A flick of light— maybe a reflection, maybe no—darted across the metal ceiling above the tracks, that same mind-bent shimmer that’s followed me ever since that Salamander night, and my foot froze. The kind of freeze that’s no fear but recognition. The train whined its ready-whine. Folk shuffled. The badge of the destination glinted. And the city said—not in words, but in that slow exhale o’ diesel and dawnlight—aye lad… not yet.

So I stepped back. One small step, then another, walked off the platform with my pulse stuttering like jazz played on a cracked horn, ticket still warm in the palm, the doors hissing shut behind me with a kind of soft disappointment that felt almost human. The train left without me— a long iron sigh fading into the dark throat of the tunnel— and I stood there breathing the city back in through the lungs, deep, sure, bone-level.

I knew then—knew it in the marrow—that I wasn’t leaving, not that day, not that way, maybe not ever in the sense that matters. Some cities do not let you go because you were theirs before you learned your own name. And Edinburgh—wee brilliant, bruised, belligerent thing—held me in its stonegrip. So I walked back up the ramp, out into the open air where the sky was still grey as a half-remembered dream, and the whole city shimmered—just a fraction—like it was glad I’d stayed.