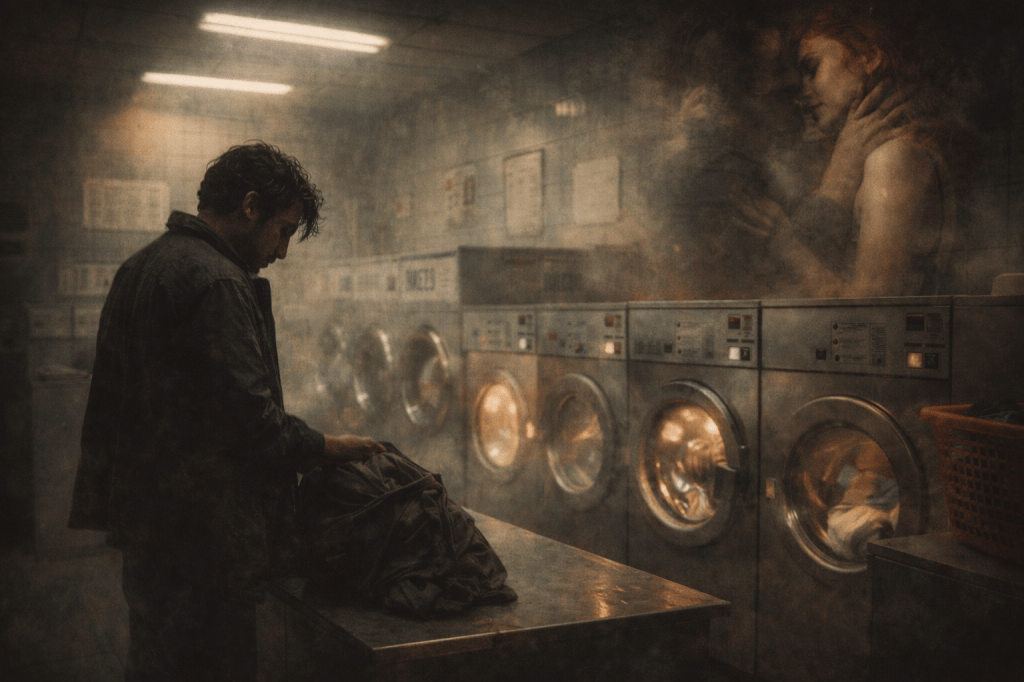

The laundrette behind Dalmeny Street buzzed like a low-slung dream-engine when I wandered in at 11:45 a.m., head thick with sleeplessness and limbs loose from last night’s unwise entanglements, and the whole place vibrated with the spin and churn of other people’s secrets—undies, sheets, neon-bright leggings, the whole sweaty parliament of city lives tumbling in soap-slick whirlpools—and as I dropped my own bag of dirt-and-nightclothes onto the metal counter I caught a sudden flicker-memory of the girl from Piershill, the one with the wicked-lantern eyes and the habit of laughing at all the wrong moments, the one who once pulled me into her narrow corridor with the urgency of a drowning woman grasping a rope.

God, her, that heartbeat-tangle of cigarettes and coconut shampoo and the sharp-sweet taste of cheap tequila she used to sip like it was penance; I can still feel the imprint of her palms on my shoulders as she shoved me against her peeling wallpaper, her breath a fast whisper in my ear—don’t think, just touch—and I remember the way she kissed like she was trying to pry open all the locked doors inside me, her teeth scraping my lower lip, her thigh hooking around mine in that clumsy, beautiful dance of two bodies trying to fill the hollow places time had carved out of us, and there in that corridor lit by a single buzzing bulb she pressed her hips into mine with that slow-grind rhythm that made my knees forget their purpose entirely.

And for a minute I couldn’t tell if I was in the laundrette or back in her hallway, and the walls sweated with July heat, and her laugh echoed in that high-giddy pitch right before she whispered something wild into my mouth—something half-true, half-dare, something like I want to disappear into you, though maybe she said I want you to disappear with me, the difference lost in the rush of lips and hands and that delirious press of skin that makes even a fool think he’s found a moment worth remembering.

I loaded the machine on autopilot, and the clothing tumbled in slow surrender, and I drifted out onto Dalmeny Street where the pavement steamed with mid-afternoon drizzle and a delivery boy biked past with the frantic grace of a fox in flight, and I followed the cracked road downhill until Shrubhill rose up, that old industrial skeleton of scaffolds and abandoned yards where I once met another woman—a redheaded muralist with paint-stained fingers and a habit of calling me “kid” even though she was barely older than me—who took me behind the half-demolished warehouse and kissed me so hard my spine rang like a bell.

I can still feel the cold metal sheet against my back and her warm palms on my stomach, sliding under my shirt in fast, greedy strokes, her breath a hot staccato against my neck as she murmured half-drunken poetry about skin and sin and how the best kisses happen in places where you’re not supposed to be, and when she pressed her chest to mine and let out that low rough moan I felt the whole world tilt, as if desire itself had seized the earth by its axis and given it a good spin just to see if we’d fall off; we didn’t, but we came close.

That whole night was a kind of improvised jazz—her climbing into my lap, my hands sliding under her coat, her thighs gripping me in that hungry lurch of wantwantwant, and me half-laughing, half-dying of need, her freckles glowing like constellations mapped across the dusk, and when she whispered there you are into my collarbone I believed, idiot that I am, that she had found something in me worth naming.

But she was gone by morning, leaving only the faint perfume of citrus paint and the memory of her mouth lingering on my shoulder like a sentence that never found its ending.

And now, standing in the skeletal half-ruin of Shrubhill, I felt the city’s breath on my neck again, that wind-slur whisper of boyo, you keep borrowing bodies like borrowed books, overdue, overdue, and I didn’t know whether to laugh, cry, or call someone I shouldn’t, maybe even the corridor girl, maybe even the muralist, maybe even the mattresswoman from Dalry Road, though each one could tear out the stitches I’ve barely sewn.

The sky broke open in a slate-grey smear, rain fell sideways in quick-cut slashes, and I ducked under the scaffolding, hands shoved deep in my pockets, my mind spinning with old touches and misplaced tenderness, and for a moment—just a hot, raw, delirious moment—I swore I felt all their hands on me at once: corridor-girl’s urgent pull, muralist’s slow-burn caress, mattresswoman’s bruising sweetness, each memory a weight and a warmth and a warning.

And the rain poured harder, the city pulsed its strange eternal pulse, and I closed my eyes and let it all wash through me—the ache, the hunger, the yes, the no, the too-much and never-enough—until the whole world felt like a single long breathless kiss dissolving into the spiral of distant laundrette drums, the spin-cycle saints still turning, turning, turning my life into something almost clean.